Impromptu in Landscape Architectecture

The Designer’s Impromptu: From Waves to Lines

In music, an impromptu is a spontaneous composition—something unplanned, flowing directly from emotion and instinct. It’s raw, intuitive, and deeply personal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxhbAGwEYGQ

And yet, many of these pieces have become timeless works, beloved and replayed across generations.

They capture something real: an unfiltered spark of the human spirit. This made me wonder—what is the equivalent of an impromptu in visual arts or in landscape architecture?

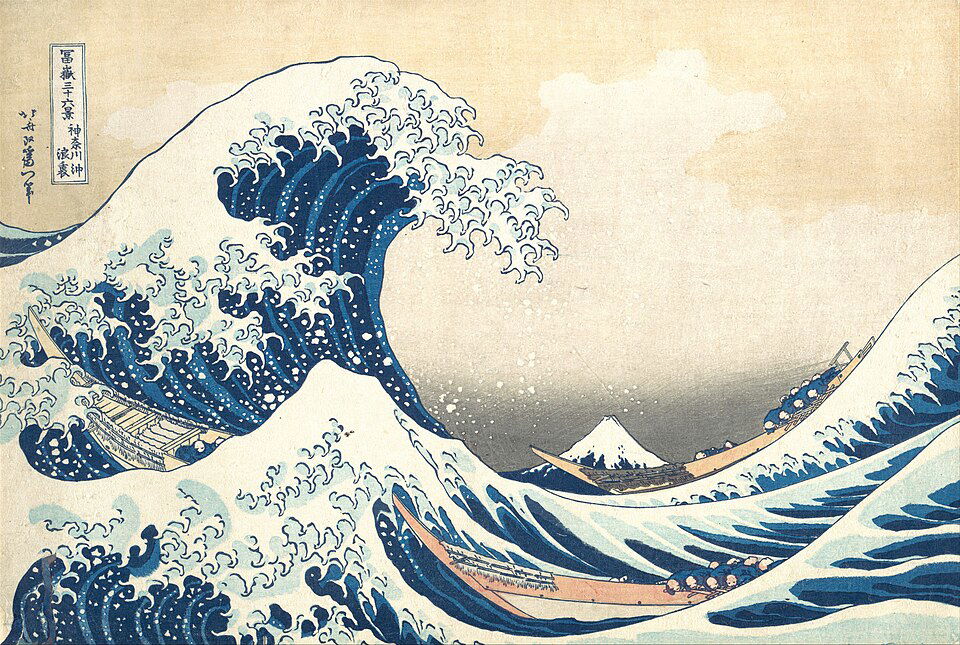

In painting, I see this most vividly in Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Though technically a woodblock print, the piece feels spontaneous. The wave crashes with emotional force, the asymmetrical balance, the smallness of the boats, and the distant Mount Fuji—it all feels like a captured instant, full of tension and motion. In a way, the piece feels like a painter’s impromptu: brief in execution but eternal in spirit.

And it became one of the most beloved and iconic images in the world.

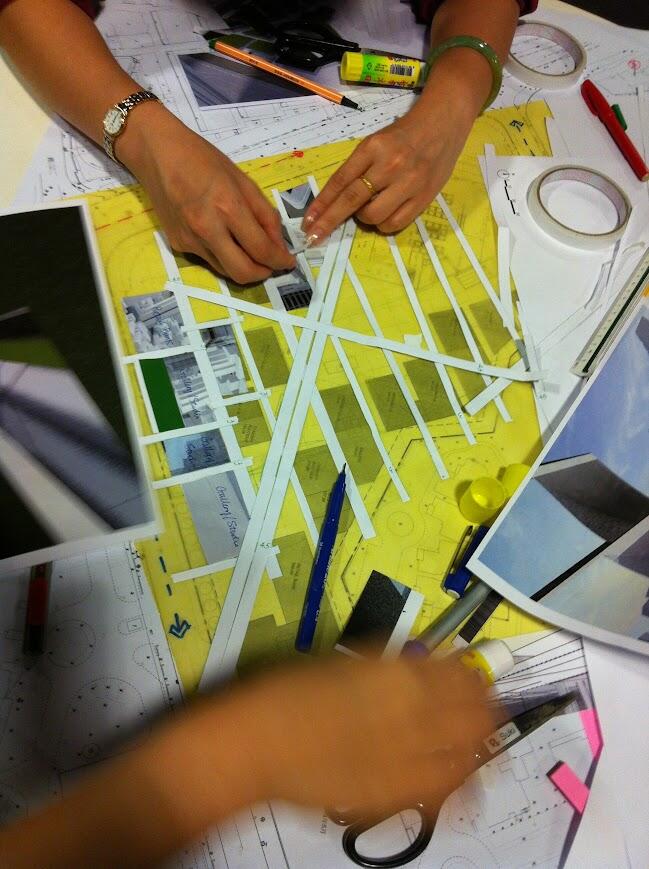

In landscape architecture, our work is often rooted in structure—budgets, regulations, grading, planting zones, and client requests. It’s rare to be given time just to design freely. Unless we initiate our own projects or enter competitions, the chance to create something purely expressive is slim. But when we do—when we sketch without instruction or constraint—we find the closest equivalent to an impromptu: the concept sketch.

A concept sketch isn’t always meant to be seen. It may look rough, unfinished, or emotional.

But it captures a pulse—an idea that hasn’t been diluted by too much logic or software. It’s where many great projects begin. These are the moments where the pen or pencil moves faster than conscious thought, and in those moments, something honest comes through.

As artificial intelligence begins to enter the field of landscape architecture and land art, it raises an interesting question:

Can AI create an impromptu? Maybe this is where AI, for all its capabilities, still has a weak spot. It can analyze precedent, automate drawing, optimize irrigation zones—but can it feel? Can it capture the shaky line of an uncertain morning sketch? Can it produce something "unfinished but complete," something that breathes on its own? The essence of the impromptu is not in perfection, but in presence—in being there, at that exact moment when the hand met the page or the note met the silence. It’s not just about the result, but the lived process behind it.

Maybe that's what we need to preserve in our profession. As tools advance, perhaps the most human part of design—the spark of the impromptu—becomes even more valuable. And maybe, like Hokusai’s wave, those instinctive gestures will live far beyond the moment they were made.